Due to their prevalence of about three episodes a year and a mean duration of five days [1], infections of the upper respiratory tract and potential complications such as myocarditis and an increased risk of muscular injuries are of special significance for athletes. This drew particularly widespread attention in association with the COVID-19 infection, but it also applies to influenza and other viral airways infections.

Initially there were few recommendations for returning to play after infections of the upper airways [2]. As the focus narrowed on the COVID-19 pandemic, recommendations on returning to sporting activities were published that were in line with the changes in the virus variants themselves [3 – 5]. Besides the individual course of viral infections, individual assessment is equally important, especially for elite athletes due to the usually more rapid resumption of training or even competitive sports. Medical evaluation in such cases poses a priority conflict between the athlete’s primary welfare and the aim of enabling the athlete to resume sports as quickly as possible.

Monitoring HRV & Orthostatic Testing

Monitoring heart rate variability (HRV) and performing an orthostatic test can serve as additional parameters for this. Since these measurements are often routinely carried out in top athletes anyway when deciding on the intensity of training, individual reference parameters for each athlete are available for comparison. The normal course of heart rate after orthostasis is as follows: the resting rate is followed by an initial rapid compensatory increase in heart rate followed by counter-regulation and a subsequent plateau compared with the supine resting heart rate, and a slightly higher heart rate when standing. The changes in heart rate and the HRV reflect changes in the autonomic nervous system. Infections are usually associated with increased heart rate at rest, with limited HRV and particularly with a higher peak of the maximum heart rate. Furthermore, there is only little counter-regulation of the heart rate, if any, when standing. Experience with SARS-CoV-2 infections showed deviations from this, often with an unchanged or even lower resting heart rate and considerably limited HRV. Nevertheless, the peak is higher after standing up, the higher heart rate persists, and there is a sharp drop in HRV [6].

Case study professional football player

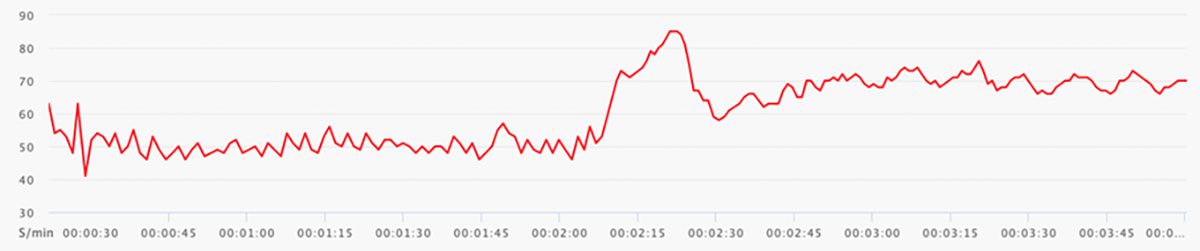

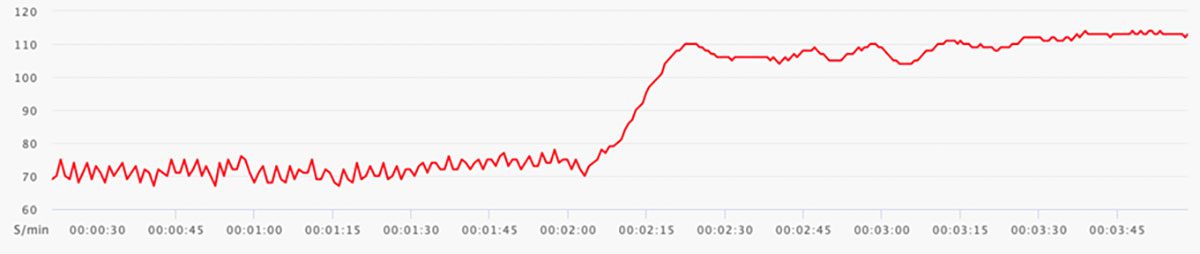

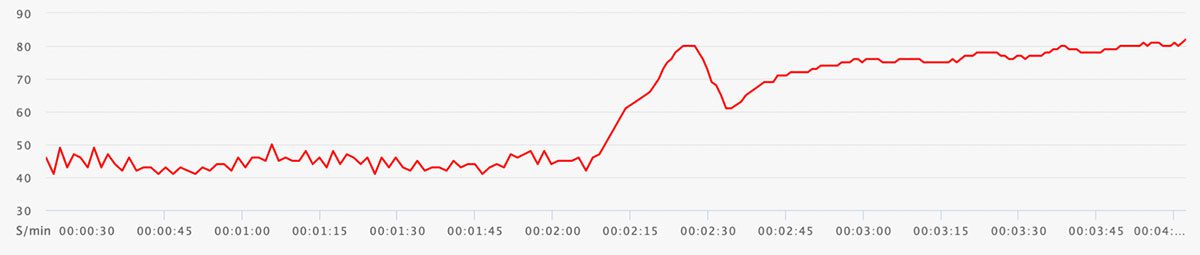

In addition to clinical evaluation we use the orthostatic test intensively in competitive sports to guide individual intensification of training during infections. We present the case of a professional football player with a SARS-CoV-2 infection as an example of this. The reference was a routine orthostatic test (Vantage V2 Sports Watch, Polar Electro) with the athlete’s normal supine HRV and good counter-regulation after standing up (Fig. 1). During the early phase of the infection this showed a higher heart rate at rest with limited HRV and the absence of any counter-regulation after standing up (Fig. 2). During this phase no sporting exertion can be recommended as this may prolong the infection with potential long-term complications. During the further course of the infection when heart rate is lower and supine HRV is better there is minor counter-regulation after standing up although heart rate is higher and increases further over time, and HRV is lower (Fig. 3). At this point in time gentle aerobic training can be started. Daily monitoring and clinical parameters decide on further intensification of training. After recovery from the infection the plot is seen to be similar to the baseline condition again (Fig. 4) with good autonomic counter-regulation. Anaerobic training is possible again. Depending on the severity of the infection, regardless of the pathogen, we recommend sports cardiology diagnostic investigations with a clinical examination, laboratory tests and echocardiography before approving competitive sports.

Heart rate at rest 50/min, HRV at rest 72 ms, peak heart rate 85/min, heart rate standing 70/min, HRV standing 16 ms

Heart rate at rest 72/min, HRV at rest 34 ms, peak heart rate 110/min, heart rate standing 111/min, HRV standing 2 ms

Heart rate at rest 45/min, HRV at rest 82 ms, peak heart rate 80/min, heart rate standing 80/min, HRV standing 4 ms

Heart rate at rest 46/min, HRV at rest 97 ms, peak heart rate 78/min, heart rate standing 65/min, HRV standing 19 ms

Summary

Measuring HRV and performing an orthostatic test are simple additional methods for evaluating the resumption of sporting activities after infections. During viral infections these show an increased heart rate at rest and, particularly, a marked increase in heart rate after standing up. HRV decreases markedly in both cases. Besides established clinical parameters, evaluation of heart rate in the orthostatic test together with HRV can be an additional tool for evaluating return to play.

Literature

[1] Svendsen IS et al. Training-related and competition-related risk factors for respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections in elite cross-country skiers. Br J Sports Med 50 (13), 2016: 809-815.

[2] Scharhag J, Meyer T. Return to play after acute infectious disease in football players. J Sports Sci. 2014; 32: 1237-1242.

[3] Elliott N et al. Infographic. Graduated return to play guidance following COVID-19 infection. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1174-5.

[4] David Salman et al. Returning to physical activity after covid-19 BMJ 2021;372:m4721

[5] Steinacker JM et al. Recommendations for return-to-sport after COVID-19: Expert consensus. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2022; 73: 127-136. ,

[6] Hottenrott L et al. (2021) Utilizing Heart Rate Variability for Coaching Athletes During and After Viral Infection: A Case Report in an Elite Endurance Athlete. Front. Sports Act. Living 3:612782.

Autoren

ist Facharzt für Innere Medizin und Kardiologie mit Zusatzbezeichnungqualifikation Sportmedizin/Sportkardiologie. Er ist Oberarzt für Interventionelle Herzklappentherapie an der Universitätsmedizin Mainz und internistischer Mannschaftsarzt des 1. FSV Mainz 05.

ist Facharzt für Innere Medizin und Kardiologie mit Zusatzqualifikation Sportkardiologie. Er ist Funktionsoberarzt der Präventiven Kardiologie an der Universitätsmedizin Mainz und internistischer Mannschaftsarzt des 1. FSV Mainz 05.