During the last year, public interest in female professional football in Germany has risen, partly due to the success of the German women’s national team during the European Championship.

In the field of sports medicine, the focus is particularly on research into the causes and prevention of injuries to female athletes.

Injuries

In football, injuries to the lower limbs, especially to the ankle and knee joints, but also to the muscles, are among the main reasons for absence from training or competition [1]. Since, in addition to the initial event, secondary injuries at the same or at a different site during convalescence also play a significant role, targeted rehabilitation is of great importance, in addition to injury prevention. While in comparison between the sexes, men are more prone to lesions of the hamstrings and in the groin area, women are more likely to suffer injuries to the quadriceps or severe knee and ankle ligament injuries [2]. For this reason, prevention strategies should be tailored to the needs of female athletes.

Male-female differences

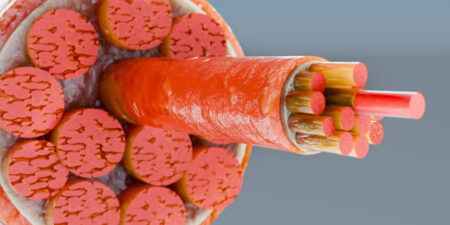

General considerations: Research into the biological differences between the sexes has increased significantly in recent years, and further findings relevant to prevention and rehabilitation are to be expected. Nevertheless, it is still the case that the majority of conclusions on optimising the aforementioned topics in professional football are based on studies predominantly involving male athletes [3, 4]. Differences exist, for instance, with regard to height, weight, muscle mass, and muscle fibre type and composition. In addition, there are also differences in maximum aerobic capacity (approx. 10 %) and in hormone household, whereby the 10 to 20 times lower testosterone levels are the main reason for the lower strength potential of women as compared with men [5].

Specifically the knee joint: Depending on the particular study, the risk of a cruciate ligament injury for women as opposed to men is about three to six times greater, especially regarding non-contact injuries. There are known anatomical and functional conditions, such as more cases of genua valga, excessive hip adduction and thus an increased Q-angle, quadriceps dominance with lower hamstring activity, increased tibial slope, narrow notch width as well as reduced trunk stability and increased femoral anteversion with the resulting internal rotation gait pattern. When comparing the sexes, this all results in creating an increased strain on the anterior cruciate ligament in female athletes. A temporal correlation of ligament injuries in female athletes, especially of the anterior cruciate ligament, can be found in the first phase of the menstrual cycle. The reasons for this range from the negative preovulatory effect of oestrogen on the tensile strength of the cruciate ligament up to a greater anterior laxity during the follicular phase. A clear additional hormonal effect on neuromuscular control has not been found [6, 7]. Whether the general risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury can be reduced by oral contraceptives does not appear to have been fully clarified [8].

Search for causes

We believe that the gender-specific differences in injury patterns can be attributed to both obvious and non-obvious causes (particularly at a professional or semi-professional level). Apart from the anatomical differences already mentioned, hormonal differences are of particular relevance. And this is precisely where the problems of finding the causes arise in practice. The menstrual cycle appears to be a common exclusion criterion for involving female athletes in trials. Menstrual cycle-dependent changes are seen as a confounding factor and, if at all, the athletes are therefore tested in isolated phases of their cycle in order to minimise their impact [9 – 11]. We regard the different financial circumstances in male and female football as a non-obvious cause. Whereas the men’s teams in the football Bundesliga are made up exclusively of professionals, players in the women’s Bundesliga often have a job or study commitments in addition. The whole focus, therefore, cannot be placed on prevention or, in the case of injuries, on rehabilitation. Experts believe that the conditions in terms of general training intensity and quality and the necessary medical and sports psychology support at a completely professional level exist in very few clubs in the first and second Women’s Bundesliga. Support with regard to athletic training or nutrition is also not comparable. It is noticeable, for example, that the frequency of injuries during matches is six to seven times higher than in training. It is therefore debatable whether training optimally prepares the players for the physical demands of the game, particularly with regard to non-contact injuries [1].

Prevention

General considerations: The current lack of data, coupled with the multifactorial causes of injury in female athletes, makes it difficult to develop an improved prevention strategy. Given that the anatomical differences cannot be changed, it is still possible to intervene in individual components of the causes of injury. In recent years, the German Football Association (DFB) has launched so-called “Performance Days” in cooperation with the University of Freiburg. In addition to medical tests, bio-mechanical examinations are also carried out at regular intervals on the selected female teams and special knowledge is passed on to the players in the form of appropriate modules. The ultimate aim is to make the players more sensitive to topics such as injury prevention and performance optimisation, on the one hand, and to use the data obtained to generate assistance in working through movement-specific and muscle-stabilising deficits and to raise awareness of typical movements and injury situations. However, this individual approach involves a corresponding financial outlay, which is not usually available to aspiring professional female football players. The further dissemination of established prevention programs such as FIFA11+ [12, 13] or eccentric strength training (the Nordic hamstring exercise) [14, 15] could lead to a further reduction in injuries, including those to the anterior cruciate ligament. These measures and focus would seem recommendable in view of the current lack of professionalism in junior women’s football and the absence of support in the field of athletics. Contrary to expectations, their use in professional football is also currently low [16].

INFO: FIFA 11+ is a standardised warm-up programme for the prevention of injuries to football players. It involves running exercises and other exercises for strength, plyometrics and balance.

Menstrual Cycle

Any general prevention strategy based on cycle-related performance and susceptibility to injury cannot be derived from current data [17]. Different performance-related parameters are affected during the menstrual cycle, but a direct impact of these parameters, and thus significant conclusions regarding recommendations and training individualisation, cannot be drawn with any certainty [18]. Based on self-reports from 1,086 female athletes from 57 types of sports, it was shown that cycle-related complaints, in particular dysmenorrhea and premenstrual symptoms, are widespread. The use of oral contraceptives appears to at least alleviate these symptoms. Only in rare cases are these symptoms taken into account when planning training and competition workload [19]. Different perceptions in relation to athletic workload differ during the individual menstrual phases.

The individual phases of the female cycle did not have an impact on the experienced level of exertion. Motivation and competitiveness, on the other hand, were assessed as better in the late follicular to ovulation phase. Mood disorders tended to occur prior to menstruation, while menstrual symptoms and a decrease in vigour were directly associated with menstruation [20]. The hormonal profile of the menstrual cycle varies both between individual athletes and between the individual cycles of one person. This poses a major problem when it comes to generalising training and prevention recommendations. The current findings are inconsistent and at times contradictory. However, there is general agreement that training and competition management should be adapted to take account of individual reactions to physical performance during the different phases of the menstrual cycle [17]. Given the assumption that match performance is not significantly affected by the menstrual cycle phases [21], it seems difficult to achieve acceptance from all participants of the concept of individualisation, especially in team sports with several players and a full-time schedule. The personalised training plan, tailored to the phases of the menstrual cycle, is much easier to implement for the individual athlete. Ultimately, recording female athletes‘ symptoms during the menstrual cycle could be useful to raise awareness of the players involved of the physical and psychological aspects of the menstrual cycle and how it affects performance.

Conclusion

Changing prevention strategies to avoid injuries while taking the needs of female athletes into account would be desirable. Causes such as anatomical and physiological gender differences can only be influenced to a limited extent, if at all. The insufficient number of isolated studies available on female athletes is problematic. Causes and prevention strategies for injuries related to the female menstrual cycle cannot be clearly and broadly identified based on the data currently available.

References

- Horan D, Büttner F, Blake C, et al. Injury incidence rates in women’s football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective injury surveillance studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:471-480.

- Larruskain, J., Lekue, J. A., Diaz, N., Odriozola, A. & Gil, S. M. (2018). A comparison of injuries in elite male and female football players: A five-season prospective study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(1), 237–245.

- Kirkendall DT, Krustrup P. Studying professional and recreational female footballers: A bibliometric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;00:1–15.

- Emmonds, S., Heyward, O. & Jones, B. The Challenge of Applying and Undertaking Research in Female Sport. Sports Med – Open 5, 51 (2019).

- Neumann, Georg (2009): Frauen, in: Martin Engelhardt (Hrsg.), Sportverletzungen, 2.Auflage München, Deutschland: Elsevier GmbH, S. 21-22.

- Balachandar V, Marciniak JL, Wall O, Balachandar C. Effects of the menstrual cycle on lower-limb biomechanics, neuromuscular control, and anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2017 May 10;7(1):136-146.

- Hewett TE. Neuromuscular and hormonal factors associated with knee injuries in female athletes. Strategies for intervention. Sports Med. 2000 May;29(5):313-27.

- Samuelson K, Balk EM, Sevetson EL, Fleming BC. Limited Evidence Suggests a Protective Association Between Oral Contraceptive Pill Use and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Females: A Systematic Review. Sports Health. 2017 Nov/Dec;9(6):498-510.

- Bruinvels G, Burden RJ, McGregor AJ, Ackerman KE, Dooley M, Richards T, Pedlar C. Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar;51(6):487-488. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096279. Epub 2016 Jun 6. PMID: 27267895.

- Meignié A, Toussaint JF, Antero J. Dealing with menstrual cycle in sport: stop finding excuses to exclude women from research. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022 Nov;122(11):2489-2490. doi: 10.1007/s00421-022-05014-1. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35984494.

- Janse DE Jonge X, Thompson B, Han A. Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Dec;51(12):2610-2617. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002073. PMID: 31246715.

- Bizzini M, Dvorak J. FIFA 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide-a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 May;49(9):577-9.

- Barengo, N.C.; Meneses-Echávez, J.F.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Cohen, D.D.; Tovar, G.; Bautista, J.E.C. The Impact of the FIFA 11+ Training Program on Injury Prevention in Football Players: A Systematic Review. J. Environ. Res. Public Health2014, 11, 11986-12000.

- Monajati A, Larumbe-Zabala E, Goss-Sampson M, Naclerio F. The Effectiveness of Injury Prevention Programs to Modify Risk Factors for Non-Contact Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Hamstring Injuries in Uninjured Team Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016 May 12;11(5):e0155272.

- Goode AP, Reiman MP, Harris L, DeLisa L, Kauffman A, Beltramo D, Poole C, Ledbetter L, Taylor AB. Eccentric training for prevention of hamstring injuries may depend on intervention compliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Mar;49(6):349-56.

- Bahr R, Thorborg K, Ekstrand J. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams: the Nordic Hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Nov;49(22):1466-71.

- McNulty, K.L., Elliott-Sale, K.J., Dolan, E. et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 50, 1813–1827 (2020).

- Meignié A, Duclos M, Carling C, Orhant E, Provost P, Toussaint J-F and Antero J (2021) The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Elite Athlete Performance: A Critical and Systematic Review. Physiol. 12:654585.

- Ekenros L, von Rosen P, Solli GS, Sandbakk Ø, Holmberg H-C, Hirschberg AL and Fridén C (2022) Perceived impact of the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptives on physical exercise and performance in 1,086 athletes from 57 sports. Physiol.13:954760.

- Paludo AC, Paravlic A, Dvořáková K and Gimunová M (2022) The Effect of Menstrual Cycle on Perceptual Responses in Athletes: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 13:926854.

- Julian R, Skorski S, Hecksteden A, Pfeifer C, Bradley PS, Schulze E, Meyer T. Menstrual cycle phase and elite female soccer match-play: influence on various physical performance outputs. Sci Med Footb. 2021 May;5(2):97-104.

Autoren

ist Facharzt für Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie mit Zusatzbezeichnung Sportmedizin. Er ist Oberarzt an der Sportklinik Hellersen sowie Teil des Teams im Prâvent Centrum Dortmund. Als Mannschaftsarzt betreut er die Frauen-Nationalmannschaft des DFB.

ist Facharzt für Orthopädie mit Zusatzbezeichnungen Sportmedizin, Manuelle Medizin, Akupunktur, Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention. Er ist seit 2013 Gesellschafter des Prâvent-Centrums in Dortmund. Darüber hinaus ist er seit 2010 Mannschaftsarzt der FrauenNationalmannschaft des DFB.