We all love watching the beautiful game and cheer our favourite team. Players seem to be part of our family. It has oft been said that the footballers’ career is a short one, and although everyone knows some footballers earn large sums during their career, this does not apply to all players.

Those having played in the lower leagues may need to find a job when they have finished playing-this obviously applies also to those who have had a career cut short due to illness or injury. Being able to work depends, in part, on good health. Although it has been reported that ex-footballers live longer, mental health problems, degenerative joint disease, and neurodegenerative disease are the cause of appreciable morbidity, which can have an impact on day to day living and working.

Health risks and problems

A survey of players in the major European leagues, despite a low response, found the prevalence of mental health problems and/or psychosocial difficulties in current and former professional footballers to be high when compared to the normal population. Burn-out (5 % – 16% current-former players) and anxiety/depression (26 % – 39 % current-former players). Low self-esteem (3 % – 5 % current-former players) and adverse nutrition behaviour (26 % – 42 % current-former players) were the issues surveyed.

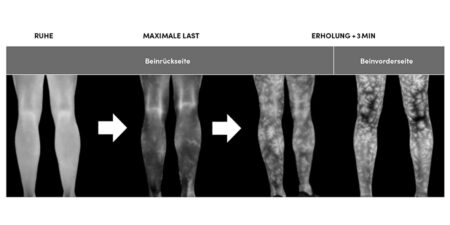

Degenerative joint disease is something that ex-players encounter earlier in their lives than the normal population, with knee osteoarthritis being twice as common, and total knee replacement three time more common. Knee pain arrives 10 – 15 years earlier than might be expected. Degenerative changes in the hip are associated with a loss of quality of life for ex-players, and daily pain and arthroplasty are significant obstructions to leading a healthy and productive life, completely contrary to the experience of being a football player.

Neuro-degenerative disease is one of the hottest debated issues in football and the effect that heading the ball and head injuries (and just participation) have on players’ central nervous systems. It is well known that dementia pugilistica was described way back in the 1930’s (Millspaugh), after being first named ‘punch drunkenness’ in the previous decade (Martland). It is also well known that some high profile players have suffered with dementia in later life. A three-fold increase in mortality from neuro-degenerative conditions was noted in a study involving Scottish ex-footballers, versus matched controls. Heading the ball has been associated with white matter changes, with one study counting headers in players over a season. Some of these players had headed the ball over 5000 times (!) in training and matches, with changes in memory scores and on MRI imaging when this figure exceeded 1800. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or Motor Neurone Disease was noted to be more common and diagnosed earlier in life in two studies carried out on Italian footballers, with a relative risk of 11 and 18 across the two studies. Not to put all the blame on football, is some information from the U.S.A. ALS registry, which states that those who have exercised vigorously before the age of 35, were more likely to be diagnosed with ALS before the age of 60, although the point was made that the causes of ALS are multi-factorial. Another multi-national study concluded that vigorous physical activity had an impact on the incidence of ALS, but an additive effect was seen in sports that involved repetitive central nervous trauma, such as football, with heading, and sustaining concussions. The now famous successful litigation achieved by players in the NFL in 2017 had a total timeline of 65 years, with $52.6 million the estimated total that would be paid out in that time. In fact, by 2018, $146.5 million had already been paid out (this is from an article in the New York Times). As stated earlier in this piece, ex-footballers do live longer, based on their lower incidence of cardio-vascular disease and cancer, but it is apparent that they do suffer disproportionate health issues after retirement, when compared to the normal population.

The question is, what should we be doing about it?!

It is clear that those in the game are trying to holistically assess the size of the problem, so that resources can be accessed and applied appropriately. One prospective pan-European study is conducting a ten year survey of footballers transitioning from the playing side of the game to achieve this. Employers in other industries now conduct ‘exit interviews’ which give guidance to the soon ex-employee as well as take account of experiences whilst employed. Doing this for footballers may iron out some of the creases involved in such an event. As well as this, the hazards and potential health sequelae are shared with the employee in other work environments prior to the commencement of a contract, so that a career is undertaken with eyes wide open to the possible risks involved. Neither of these practices occur formally in football.

There is money in the game, and to set up any service will take resources. If, after their playing days, we are to support those who continue to entertain us, whether from our sofas or from the terraces, we need to determine what is needed, and undertake to provide such support.

Autoren

is a Consultant in SEM in the UK. He started worked in professional football in 1987, working for 4 EPL clubs, as well as the England men's national team. He currently works with the global performance unit at Manchester City, and for the Royal Ballet Company in London. He has attended 3 Olympic Games as physician, and two senior, one under-20 FIFA World Cups, and two UEFA European Championships. He is a board member of the International Concussion and Head Injury Foundation, and lectures regularly to postgraduates on football medicine. He is due to work as a Venue Medical Officer at the FIFA World Cup in Qatar.