Muscle and musculotendinous injuries are among the most common pathologies in team sports involving fast-paced movements in certain game situations. The sprint in football resulting in muscle fibre tears of the hamstrings is a particularly good example of this (Sportreport of the VBG 2021, the German Employer‘s Liability Insurance Association). But American football is also notable for the extreme strain it places on muscle and tendon tissue, for example when the running backs sprint or the defensive line intercepts the opposing quarterback.

In the latter game situation, the defensive ends must as quickly as possible prevent the opposing team‘s quarterback from setting up play during the pass rush or, ideally, sack him (bring him down) or block the running back‘s path. The defensive ends are usually tall and heavy. Nevertheless, they have to be extremely fast for their key role in the game. Therefore, a large mass of often 120 kg must be accelerated to its maximum. In our case, the player is 194 cm tall, weighs 115 kg, and can run the 40-yard dash (approx. 37 m) in 4.8 seconds. In this case study, we present a multimodal treatment concept for a muscle tear, which led to a pain-free return to competitive sport after just five weeks. Here, as always, the interindividuality of each patient must be considered. Additionally, the season in American football (in this case the European League of Football (ELF)),which is very short as compared with other team sports, creates a certain degree of pressure to succeed.

Case study

In mid-July, the 27-year-old defensive end player of the Hamburg Sea Devils suffered a muscle tear of the medial head of his gastrocnemius during sprint steps in the 4th quarter of a season game. At that time, the very short three-month regular season of the ELF to qualify for the play-offs was about halfway through. Until then, the player had been able to take part in training and matches without any significant restrictions or injuries. Furthermore, he had suffered no previous injuries to his calf muscles.

Diagnostics

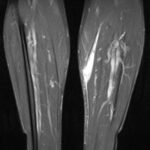

The MRI scans of the left lower leg obtained after the injury demonstrated a substantial, semi-circumferential medial fluid collection along the superficial soleus fascia. There was oedema within the medial head of the gastrocnemius which showed a circumscribed haematoma measuring 12 x 29 mm. In addition, there was an extensive lamella of fluid extending to the anterior margin of the tibia. The retracted tendon core of the medial head of the gastrocnemius was evident at the inferior margin of the haematoma, at the level of the middle third of the tibial shaft (Figs. 1 + 2).

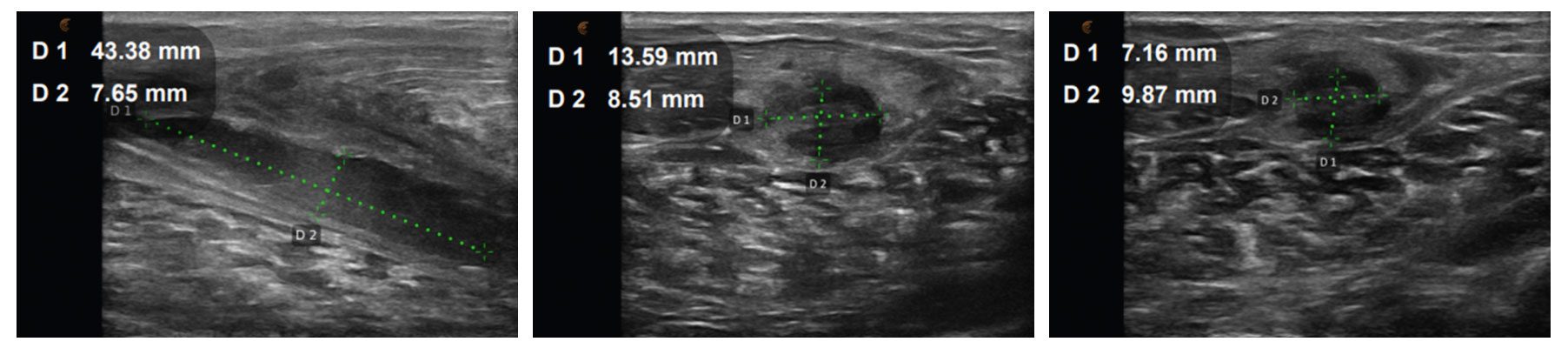

On clinical examination, the patient reported significant pain of the muscle on stretching and pressure. Distal perfusion, motor function and sensory function were normal. One week after the MRI examination, the first follow-up ultrasound scan was obtained. No continuous pennate appearance of the medial head of the gastrocnemius was evident, only mild residual seroma, while elastography was unremarkable. Further ultrasound scans were obtained every seven days to monitor progress (Figs. 3 – 5). At each review appointment, the temperature on the contralateral side was also measured (Delta T), and the visual analogue scale (VAS) was recorded to quantify the pain.

Treatment

The multimodal treatment concept comprised the following components:

In the acute phase (Delta T > 1.2 °C, VAS > 4, significant pain on stretching and pressure):

- Application of a zinc paste dressing

- Application of a calf muscle bandage for compression and stabilisation

- Neuroreflectory hyperbaric CO2 cryotherapy (directly to the lesion and along the course of the efferent lymph vessels, 4 x /week)

- Radial shock wave therapy

(applied carefully directly to the lesion and along the course of the efferent lymph vessels, 4 x /week) - Induction therapy (capillarisation programme, 4 x /week)

In the subacute phase (Delta T >1.2 °C, VAS > 4, mild pain on stretching and pressure):

- Neuroreflectory hyperbaric CO2 cryotherapy (directly to the lesion and along the course of the efferent lymph vessels, 4 x /week)

- Radial shock wave therapy (applied carefully directly to the lesion and along the course of the efferent lymph vessels, 4 x /week)

- Induction therapy (capillarisation programme, 4 x /week)

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the gastrocnemius muscle (atrophy programme, 2 x/week) active, eccentric, while standing on the edge of a step

In the subclinical phase (Delta T < 0.8 °C, VAS 1 – 2, no pain on stretching or pressure):

- AlterG Anti-Gravity Treadmill (high starting speed up to 16 km/hr, 50 % body weight, 2 x/week)

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the gastrocnemius muscle (atrophy programme, 2 x/week) active, eccentric, while standing on the edge of a step

- Radial shock wave therapy (applied directly to the lesion and along the course of the efferent lymph vessels, 4 x /week)

- Start of American football training (with tape / calf muscle bandage) involving cutting manoeuvres, acceleration runs, etc.

The aim of this treatment concept was initially to relieve pain and reduce effusion and to improve the local metabolic situation. This was followed by functional therapy to meet the demands placed on the calf muscles of a defensive end as far as possible and to simulate them.

Fig. 6 Neuro-reflective hyperbaric CO2 cryotherapy / Fig. 7 High-energy inductive therapy/ Fig. 8 Neuromuscular electrical stimulation with eccentric training

Morphological clinical course

The symptoms had already improved noticeably after about a week, so that the intensity of the radial shock wave was gradually increased (by increasing the pressure from 1.5 bar to 2.5 bar). At the same time, the follow-up ultrasound scan after seven days showed a clearly reduced effusion. Twelve days after the injury, additional eccentric training of the calf muscles was already started. The intensity was continually adjusted from one therapy session to the next. This also meant that intensity needed to be reduced whenever muscle soreness became a significant problem. Sixteen days after the injury, the patient started treatment on the AlterG Anti-Gravity Treadmill, which was alternated with NMES-controlled eccentric training. Whereas cryotherapy was no longer used once the subacute phase was over, radial shock wave therapy remained a basic component of the treatment and was applied after the patient had done initial active exercises. The ultrasound examinations continued to show a reduction of the effusion. Four weeks after sustaining the injury the patient was free of pain for the first time. Another five days later and two days before the next league match, the patient was given the all-clear to play (with white tape for compression). The decision criteria here were the absence of pain on stretching and pressure, the almost continuous pennate appearance of the muscle and only slightly visible residual effusion on ultrasound. The patient was able to complete both the competitive match and the training session the following day without any discomfort.

Conclusion

The reported case shows us that a multimodal treatment concept together with close monitoring plus adapted therapy and exercise management can be an effective form of treatment for musculoskeletal injuries. Apart from the clinical examination and the patient‘s own subjective perception, this was also confirmed by the imaging procedures. A non-invasive and drug-free treatment concept was adopted as a basic rule, which may well also have had a positive impact on patient compliance. So far, the patient has not suffered a recurrent injury and has been able to play all the remaining games of the season.

Autoren

ist Facharzt für Orthopädie, Chirurgie und Unfallchirurgie, Sportmedizin und Notfallmediziner. Er ist leitender Arzt der orthopädischen Privatpraxis Sporthopaedic Hamburg und Head of Medical Commission der European League of Football (ELF).