The treatment of muscle injuries is based first on the physiology of muscle healing, and second on the site and severity of the injury. The “Munich Consensus Classification” according to Dr Müller-Wohlfahrt and the “British Athletics Classification” are most commonly used to assess the severity of the injury. While the first also takes ultrastructural injuries into account, the second is considerably more clearly differentiated regarding the structural lesions.

It also takes into account the localisation within the musculature and possible involvement of the intramuscular tendon, and classifies the extent of the injury depending on the cross-section of the muscle. A correlation with the total downtime in professional football has been proved for the Munich Classification. If there is no evidence of a structural injury it is vitally important to search for possible neuromuscular causes or muscular imbalance as the precipitating factor, especially in repeat cases.

Physiology of muscle healing

The physiology of muscle healing is divided into different phases, some of which overlap and affect each other mutually. During the first so-called “degeneration phase” the destroyed structures undergo controlled breakdown followed by an inflammatory phase in which myoproliferation begins, and a repair and regeneration phase during which the myoblasts differentiate and form myotubes which then coalesce to myofibrils, thus repairing the injured muscle fibres. Some of the cellular and cytokine processes in the individual phases run consecutively, others also overlap. Inflammatory processes occur both in the early phase of the injury (between about days 2 to 7) as well as in the late phase. In this context the inflammatory processes most certainly have positive effects, so according to our current understanding, they should not be completely suppressed by drugs. Thus it is recommended to stop the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents which are used initially to relieve pain after 48 hours and to replace these with plant-based preparations (e.g. Wobenzym®, Traumeel®).

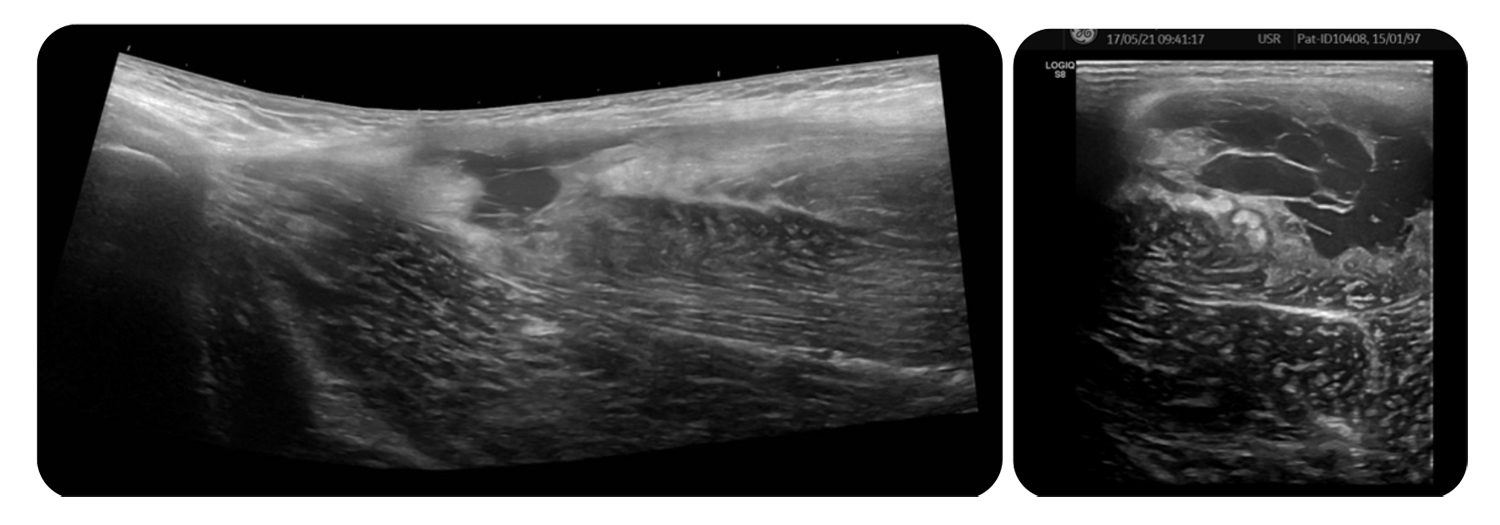

During the initial phase of the injury cooling and compression are the most important measures for reducing the extent of the injury and the haematoma. The so-called “PRICE” scheme (PRotection = immediate interruption of the exercise, Ice = cooling, Compression and Elevation) or the “POLICE” method (Protection, Optimal loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) has become established in this respect although the clinical data on file is limited, even for these simple measures. However, a new paper by Hotfiel et al. illustrates very clearly that the combination of compression and cooling achieves an adequate reduction in the blood flow without a subsequent rebound effect when it is removed. Rapid compression and immediate cooling after an injury are essential to prevent the formation of a haematoma – which in turn compromises healing. The rule of thumb that “every minute treatment is delayed prolongs rehabilitation by one day” underlines the importance of treatment within the first half hour after the injury. Maximum pressure should be exerted for the first 20 to 30 minutes, followed by moderate compression for the first 48 – 72 hours. Cooling is best achieved with sponges soaked in iced water, later in professional sports with commercially available long-term cooling systems such as Game ready® or Hilotherm®. Conversely, if relevant structural damage has occurred, immobilisation is kept very short. A relevant haematoma should be aspirated as early as possible, ideally within the first 36 hours. However, in the author’s opinion, attempted aspiration later under strictly sterile conditions for larger haematomas or seromas is very useful for achieving rapid healing, even if this is incomparably more difficult with coagulated blood. The early phase is followed by the structured rehabilitation process which is guided by subjective pain perception and should be directed by specific functional tests. For instance, the ASPETAR protocol has reviewed this very nicely for hamstring injuries; the protocol is available on the Internet for a free download.

after ultrasound-controlled puncture of the hematoma.

Supportive treatment

Supportive treatment includes support bandages with tape or supports (incl. Myotrain®), nutrient supplementation, physical measures (ultrasound, shockwave therapy, magnetic fields) and infiltration. The most commonly used substances here are homoeopathic complex preparations such as Traumeel® and Zeel® as well as Actovegin® and Myopridin®, local anaesthestics and PRP/ACP. Clinical studies of different forms of infiltration treatment are unfortunately still only available in very limited numbers, although in vitro studies have revealed the mechanisms of action and very promising healing results in animal models. For instance, Actovegin® increases myoblast activity and satellite cell activation, so that its use during the initial phase of muscle healing between days 3 and 10 can be recommended. However, there is evidence of this from clinical studies, and it must be pointed out that as the preparation has not been licensed in Germany or Switzerland, patients must be informed about its off-label use.

Traumeel contains 14 mainly plant-based constituents including arnica, calendula and echinacea. In animal models the preparation showed a reduction of inflammatory activity and stimulation of the repair mechanisms by stimulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines (incl. TGF-β ↑ (regulatory T-cells) and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8). The hypertonic part of the muscle can be relaxed with local injections of muscle relaxants and local anaesthestics. By contrast, cortisone preparations are obsolete. With regard to the PRP preparations, which are now in very common use, as the current data on file suggest a shortened return-to-sport time, in our opinion they are most certainly justified in professional sports. On the other hand, it remains to be seen whether we may expect better healing results or lower relapse rates.

Adjunctive manual therapy and physical measures support the muscle relaxation of hypertensive parts of muscle and the return transport of lymphatic fluid. Close clinical and ultrasonography follow-up examinations are recommended to monitor the course of healing and to react to demarcating (haemato-)seromas. Structural remodelling should be verified, particularly for injuries prone to recurrence and with involvement of the intramuscular tendon to ensure a safe return to sports. In closing it must be noted – without going specifically into it in this article – that preventive programmes are capable of very effectively reducing the prevalence of muscle injuries – but only if they are carried out. Therefore, athletes, coaches and staff should never tire of taking every possible opportunity to stress how important these are.

with a demarcated loculated seroma.

Autoren

ist Fachärztin für Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie und leitende Ärztin am Altius Swiss Sportmed Center in Rheinfelden / Schweiz. Sie ist seit 2007 leitende Verbandsärztin der dt. Nationalmannschaft Paracycling und seit 2017 leitende Ärztin Leistungssport des Deutschen Behindertensportverbandes. Außerdem ist Professor Hirschmüller u.a. Mitglied des Wissenschaftsrates der DGSP, Leiterin des Expertenkomitees „Konservative Therapieverfahren und Rehabilitation“ der AGA sowie Mitglied des GOTS Komitees Muskel/Sehne. 2021 wurde sie GOTSSportärztin des Jahres.